The Toddler Morning Efficiency Curve

March 1st, 2015 by PotatoIn all my years and all my learning, I have never quite got the hang of mornings. I used to be pretty good at sneaking up on them from the other side, staying up all night to get them when they least expect it, but waking up and facing a new day is just such an impossible concept. I know some people can basically just roll out of bed and be something called “chipper” and “alert”. I am not one of those people. I used to play snooze-button basketball with my alarm clock to gradually wake up over the course of an hour and a half, then search for caffeine before risking communication with other humans.

At several points in my life I have studied the evidence and become convinced of the utility of breakfast, and have woken up early to eat this mystery meal before leaving for work. Inevitably, after a few weeks of that I decide (consciously or not) to forgo breakfast in exchange for more time in bed, or less stress at cramming the rest of my routine into an unrealistically short period of time.

And time is the big problem with mornings: it doesn’t behave or flow right. I can sit there at night, when everything is sparkly and sleek and working as it should, and time myself as I perform the necessary house-leaving preparatory tasks to plan when I need to haul my ass out of bed for the morning. I can put two poptarts in the toaster, determine that it takes 90 seconds to toast them, 25 seconds to slather them with peanut butter, and all of 195 seconds to shovel them into my food hole and wash them down. Practice run done: 310 seconds for breakfast, add it to the morning time budget, set the alarm clock back appropriately and we will be able to squeeze breakfast in. But then morning comes and time stops working properly. My carefully practiced and timed breakfast routine goes horribly awry. It’s going on 12 minutes and I still have half a pop tart to eat and somehow there’s melted peanut butter dripping on my pants.

I cannot accept that this is merely a subjective time dilation effect, caused by my severe case of night owlism. My toothbrush has a digital timer so that I brush for precisely 2.0 minutes. Yet in the morning, even though it still ticks up towards 2:00, it takes five minutes to get the whole process over with — the morning effect clearly affects even piezoelectric crystal-based time measurement.

Anyway, all this is to say that I am “morning challenged” and pretty much always have been.

Then into my life comes a wonderful bouncing baby, who becomes an amazing little toddler girl. Now instead of an alarm clock I wake up to the sound of “Daddy! Come pleeeeeeeeeeeeeease!” Bopping her on the head does not get me an extra 15 minutes to snooze so I pretty much have to get up at that point. For a long, long while she was waking up too late for me to even see her before I left for work, but then over the last year that has flipped so that she wakes up crazy early, following the ancient toddler urge to be up before dawn so that they can watch the sun rise and ask “why?”

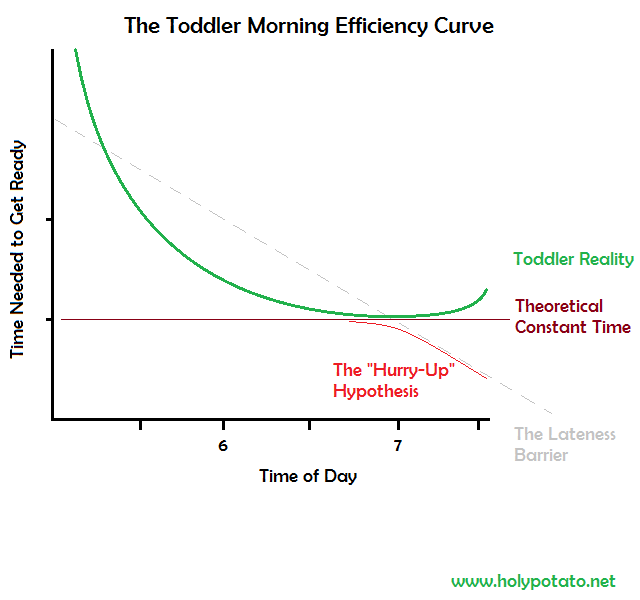

And while to me it all sounds universally crazy early, there is a big difference to waking up at 5:30am and 7:00am, and incredibly it leads to a totally non-linear relationship in the time to be ready for work, a function I call the Toddler Morning Efficiency Curve. You would think that it would take about the same amount of time to do basically the same sets of things each morning, no matter when your wake-up call happened to come in. Indeed, if there was a non-linearity, you’d expect to become more efficient as the time to get out the door for work came closer and you started to hurry or cut non-essential things out of the routine — the hurry-up hypothesis. But it’s not so simple.

If she wakes up at a “normal” time (normal for her, not for me), let’s say 6:30 to 7 am, then things proceed reasonably well. We can spend 10 minutes or so where I am just a useless bag of shambling meat, a zombie barely able to greet her and see if she needs a diaper change immediately or if it can wait a few minutes for the strength and dexterity to return to my hands. At some point shortly after waking up, I can go potty, tell her that I’m about to go potty, reassure her that I will be back in just one minute, and then go potty and listen to her wail for daddy to come back because this is a surprising and distressing abandonment and not something we do every. single. day. that daddy always comes back from.

Then we’ll get her dressed, maybe have some time to read a few books, play for a bit, or watch an episode of Mr. Rogers, then we go wake mommy up so I can have a shower and get dressed myself.

If she wakes up later, we can cut down on the playing or TV watching, but then have to deal with the whining that happens around the severe and unfair deprivation we’re causing through that action. The bigger issue though is that sleeping in just a bit seems to activate the lazy sunday lay-in region of her brain (the posterior cingulate? it’s got to be used for something, and seems to deactivate with any other active behaviour) and she no longer wants to get dressed. She wants to wear her PJs all day.

Even more inexplicable and fascinating is the phenomenon of waking up earlier. So many early theorists in parental dynamics predicted that if you had more time in the morning, you would at worst be finished everything by the same deadline — that the lateness barrier could not be breached from the left-hand side of the curve. How wrong we were.

Instead, we have the case where daddy is a nearly-immobile shuffling zombie, eyes 75% closed (often one closed entirely and the other largely closed against the harsh light of a 10 W night light), while the toddler draws unholy manic energies from the predawn night and tears circles around him. When it’s time to get dressed, she becomes and impossible squirming octopus of giggles, pleased as punch that she can so easily avoid having clothes put on her, free to live out her dream of running around the house naked.

Add to this the propensity for shuffling-sleep-zombie daddy to collapse onto any bed, couch, or other soft-looking surface “for just one more minute” of “inspecting his eyelids for holes”, and the whole thing becomes non-linear: the delays and funny effects on the flow of time from the early morning start using up more time than the extra head start provided in the first place, and everyone ends up late for school and work.

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948 Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.

Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.