CPP Calculator with CPP Enhancements

December 16th, 2016 by Potato“How much CPP will I get?” is a common question, and an important one that will help feed your financial planning. You can get a statement detailing your CPP contributions from Service Canada, but unless you’re close to retirement this isn’t super-helpful for planning purposes because it’s harder to do what-ifs with it. Indeed, it will basically assume that you’ll continue earning at your current rate until a given age, which is not helpful if you’re trying to evaluate early retirement scenarios. Plus, it’s a fair bit of work for precision when you may just want a good enough estimate. There’s also a calculator at Service Canada that includes the CPP, but it’s web-based so not great for playing around with, and it doesn’t do a good job of incorporating changes to future income, nor does it appear to be updated for the changes to CPP (announced in 2016, and partially implemented now).

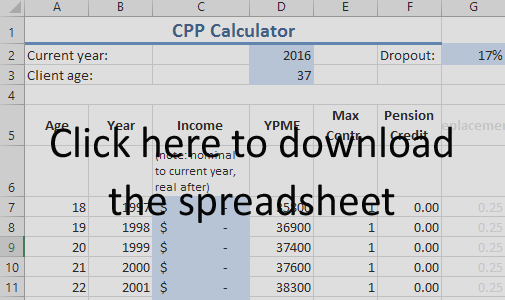

So I’ve built a spreadsheet to let you do just that. Click here to download it (Excel) (updated for 2022’s YMPE) (or here for OpenOffice). Keep reading for details on the calculations and how to use it.

Background and Acknowledgements

This came about because Sandi Martin came to me asking how to solve the problem of estimating the future CPP for people that would partially benefit from the changes to CPP announced in 2016 (which will be slowly implemented over the coming years). She had a spreadsheet for the old calculation, but I pretty much started from scratch to build this in. Having her sheet in front of me as I did so was helpful, and she was instrumental in the testing and trouble-shooting.

This post by Doug Runchey was hugely helpful on the algorithm CPP uses, which is not as intuitive as you would think. Doug offers a service to calculate your CPP precisely, so if you need to know down to the last dollar how much you’re going to get, contact Doug and pay him to run that calculation for you. Update: Doug and David Field have combined to create a web-based calculator here. If you can upload a statement of contributions, that will be more convenient. If you want to play what-if games or have to enter your data manually, then my excel version will be more convenient (in part because of the fill down function of excel, and also because mine won’t give you errors if you enter an amount above the YMPE).

Instructions

Simply fill out the boxes shaded blue, then scroll down to see how much your CPP is. The year and age should be self-explanatory.

Dropout: You’re allowed to drop a certain number of years from your CPP calculation. This lets you have a few years of low/no earnings and still collect the maximum CPP. Right now you’re allowed to drop 17% of your working life (over at CPP it’s actually in months but the spreadsheet uses years). So the number of years that works out to depends on when you collect CPP. However, there are cases where you can use the child-rearing provision to drop more years — use this field to add those drop-out years, in percentage form. Note that if you’re adding years as a percentage, now you’re making an assumption on when you’ll take CPP, so the table at the bottom will have further approximations for you.

Income: Enter how much you earned each year towards CPP. For years before 2019 enter the actual amount in that year’s dollars. For years after 2019, use real dollars. That is, if you’re earning $50,000/yr now (just a bit under the YMPE), and next year expect to get a cost-of-living raise only, enter $50,000 for 2018 — you’ll still be at the same fraction of that year’s CPP maximum. If you’re expecting a 4% raise — 2% cost-of-living, and 2% real increase in pay, then enter that increased amount above inflation for the future year ($51,000 in this example). And that continues for future years: if 10 years from now you expect to just pace inflation, keep filling in the same salary figure in 2019 dollars.

Otherwise, have fun exploring your what-if scenarios for when you stop working, etc.

Results

Keep scrolling down past all the years to enter your income history, and you’ll find a little table with the results — how much you can expect to earn from CPP annually. This includes the bonus/penalty for waiting to take it/taking it early, so you can quickly see about how much you’ll get for taking it at different points.

Approximations

The calculation should give you your CPP benefit to the nearest 5% or so (several people have sent me their statements of CPP and even for those collecting under the old system, there are differences of ~1-3%). I’m happy with that level of good enough — after all, you can get about that much difference just from deciding whether to enter your age as of the beginning of the year or the end of the year. If you need more precision, lookup Doug Runchey’s service.

CPP is actually based on months of contributions (and months of drop-outs, etc.). Here I’ve just rounded off (discretized) to years, which is going to cause a bit of discrepancy. This will also cause a slight issue in the table of results for taking CPP at different ages, as whole years of drop-out pop up at 62 and 67 (vs. the more gradual inclusion of drop-outs when you discretize to months).

You can drop extra years for the child-rearing provision, however there are some extra rules about the dropping out that the spreadsheet doesn’t account for. If you add extra percentage drop-out for child-rearing, that’s not necessarily going to translate into the same years dropped out at each age for taking CPP, so it will be less accurate if you’re including extra drop-out years for disability or child-rearing. On top of that, there has been concern that the drop-out provisions wouldn’t apply to the enhancements, though with several years to the enhancement roll-out this may yet get patched. To assume the CBC article is how it will be (i.e., it won’t get patched), reduce your drop-out by ~33% for years after the full implementation.

The five-year average rule for determining the pension payout is hard to apply in the future where the inflation rate is unknown, so I’ve assumed an inflation rate similar to that of the last 5 years.

Why Doesn’t This Match My Service Canada Estimate?

There are a few places where the government has put up CPP estimators. If you ask Service Canada for your CPP estimate, in the very fine print you’ll see a note about the assumptions used, including that they estimate that you will continue to contribute at the same portion of YMPE until age 65 that you averaged until the date of the statement. So if you had a few years off or lower-paying jobs in your younger days, you might only be averaging 0.9 or 0.8 of the YMPE, and even though you’re earning well over that now (and punched into the spreadsheet that you’d keep going at it to 65 at that rate), the government’s statement assumes a lower continued contribution. Similarly, some people assume that because they didn’t provide any info, the pension figure applies even with no further contributions, yet entering 0 for future years in the spreadsheet results in a lower estimate. The Retirement Income Calculator they put up likewise has issues, not including the enhancements to CPP announced in 2016, as well as other issues.

Commentary

I was actually somewhat shocked as I went through this at how mis-leading the initial government release on the CPP enhancement was. I had seen the “upper earnings limit will be targeted at $82,700” in all the news stories — which sounds substantially higher than today’s ~$55k figure. What I didn’t see was that this figure was not in today’s dollars, but in 2025 dollars, and that they assumed a rate of inflation close to 3% (well above the recent experience) — in today’s dollars, the new upper limit is actually just $62,586 (14% higher).

I was also surprised at some of the little things in the calculation, like that the payout is based not on the YMPE level when you start collecting, but a lower number (the average of the previous 5 years). I can’t fathom the point of this step of the calculation.

Otherwise, I haven’t seen explicit information on precisely how the CPP enhancements will be rolled out, but have made reasonable guesses as to how they will be pro-rated. What are the CPP enhancements, you ask? In short, an increase to the maximum amount you can contribute to CPP (so it will cover more of your income if you earn more than the maximum now), and an increase to the amount of income CPP will look to replace (from ~25% now to ~33% for those in the future). These were announced in the summer of 2016, and will start being phased-in in 2019 over the course of 7 years.

Updates

Version 2: Adjusted the age 66-70 calculations to keep using 48 years as the number of contributory years as part of the over-65 drop-out provision (see comments). Also rolled forward the calculations for 2017’s YMPE.

Version 3: Rolled forward to 2018’s YMPE. Also added the year’s basic exemption (YBE), which has been $3500 for a while (my entire working life) — if you earn less than that, the sheet will now zero out your pension credit. While the exact CPP calculation is hard to dig up, every source I find indicates that yes, if you earn over the YBE you still get credit for the full amount of your earnings even though you only pay on the portion over that. That is, if you earned $4000 last year, you only paid CPP contributions on $500 of that, but the full $4000 is used to figure your pension credit (e.g., the example in this post by Doug Runchey, where someone pays $0.05 to get a pension benefit of $21/yr when just over the YBE).

Version 4: No major changes, just rolled forward to 2019’s YMPE.

Version 4a: Thanks to Craig B who pointed out a (likely) error in the number of contribution years — it looks like I was including the year of retirement itself, rather than the natural assumption that if you’re taking CPP at age 65 that you do so essentially on your birthday, not after another year of working at 65. It would be a fairly small error for most cases (within that ~2-5% anyway), but good catch! I say (likely) error above because it’s late and my brain is fuzzy after just submitting a grant, and I haven’t had time to check the revised version against the various real test cases I had for verification, but I’m pretty sure this was a minor error and have put up version 4a. I will adjust this message and roll the version number up to 5 after I have a chance to think and test further (and there is a small chance I just introduced a minor error instead — but again, only another ~2% off). You can download version 4 here (or the link above for v4’s notes) if you want to check both ways.

Version 5: No major changes, just rolled forward to 2021’s YMPE. Note that 2020 was a garbage fire of a year, so there was no version between 4a (up to 2019’s YMPE) and 5 (2021’s YMPE).

Open Office Calc version of V5: trying to bring the Excel version into Open Office broke all of the INDIRECT() cell references at the bottom. I’ve fixed that in this version, and everything appears to be working the same as in excel version 5.

Version 6: No major changes, just rolled forward to 2022’s YMPE. And here is the open office version of the same.

Once again, click here to download the CPP calculator (Excel). (or here for OpenOffice).

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948 Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.

Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.